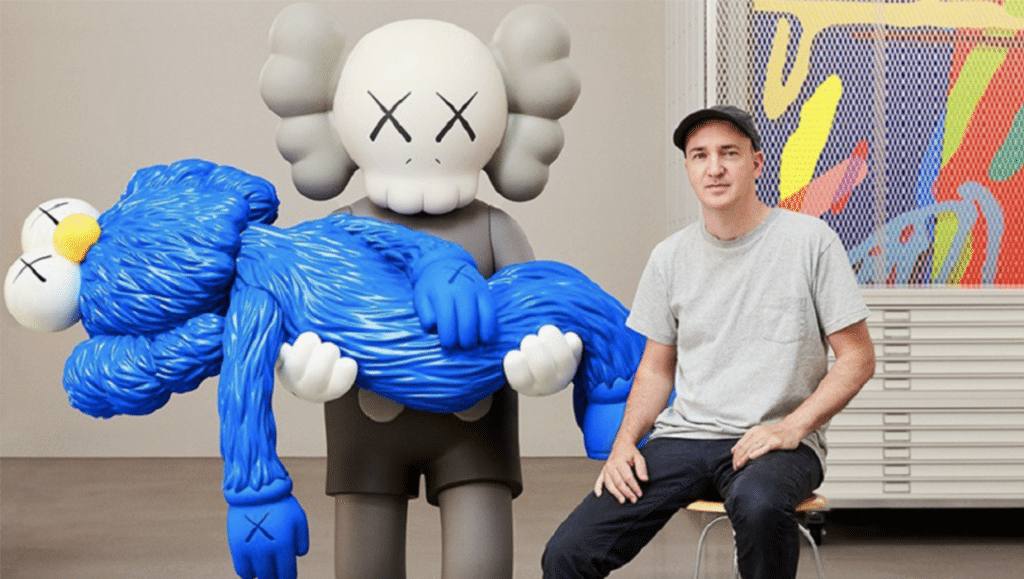

Beyond KAWS: The Art Toys

The art toy is designed by an artist and produced by small boutique factories in various materials and colorways.

Anyone can take home a KAWS—whether it’s the avid designer-toy collector scoring a $200 MoMA store edition or the fine-art collector bidding in the millions for a large-scale “Companion.”

The underlying ideas behind the designer toy movement have largely remained the same since they were first introduced in Asia in the mid-1990s: Create a character that would be popular with kids, and twist it into something edgier, more adult.

But are designer toys, in fact, art? That’s a question that has followed Budnitz since the beginning, and his answer has always been “yes.”

But are designer toys, in fact, art? That’s a question that has followed Budnitz since the beginning, and his answer has always been “yes.” It’s the art world that needs to catch up—and it is. Budnitz believes this is because fine art and pop culture are moving closer together—a shift he likens to the way streetwear became high fashion. He points to artists like Eaton, Futura, and Gary Baseman, who have all seen their audiences expand through designing toys. “I think culture has come to them,” he mused. “I think part of it is they’ve stuck [with] it. [But] I think culture is now completely heading exactly in the direction of what we’re doing, and what a lot of these artists are doing.”

This article is taken from artsy.net and written by Jacqui Palumbo. Cover image by Ozan Tekin